| Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Basic Information

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a cancer of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell involved in the body’s immune system. Lymphocytes are normally found in the blood, lymph nodes, bone marrow (the spongy, red tissue in the inner part of the large bones), spleen, and in a clear fluid called lymph that flows through small vessels in the body and collects in lymph nodes.

In patients with CLL, mature lymphocytes grow abnormally and accumulate in the peripheral (circulating) blood, bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes. Over time, these malignant (cancerous) cells may crowd healthy blood-forming cells, resulting in fewer red blood cells (which deliver oxygen to the body), neutrophils (a type of white blood cell needed to fight infection), and platelets (which prevent bleeding). CLL often grows and progresses slowly, and it may take years for symptoms to appear or for treatment to be needed.

There are two general types of CLL, and it is important for doctors to assess whether the disease is caused by the overgrowth of T cells or B cells. T cells and B cells are specific types of lymphocytes. T cells normally help to fight infections by activating other cells in the immune system, while B cells are part of the antibody-producing machinery of the immune system. The T-cell type of CLL is less common (about 1% of all CLL cases) and progresses more rapidly than the B-cell type of the disease (more than 95% of all CLL cases).

Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that increases a person's chance of developing cancer. Some risk factors can be controlled, such as smoking, and some cannot be controlled, such as age and family history. Although risk factors can influence the development of cancer, most do not directly cause cancer. Some people with several risk factors never develop cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. However, knowing your risk factors and communicating them to your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health-care choices.

The cause of CLL is unknown. There is no proven link that exposure to radiation, chemicals, or chemotherapy increases a person's risk of developing CLL. The following factors may raise a person's risk of developing CLL:

Family history. Approximately 20% of patients with CLL have a relative with CLL or some other lymph-related cancer.

Age. CLL is most common in older adults, is rare in young adults, and virtually never occurs in children. About 90% of people diagnosed with leukemia are over age 50.

Gender. CLL occurs more frequently in men.

Ethnicity. B-cell CLL is more common in people of Russian and European descent, and virtually never occurs in people from China, Japan, or Southeast Asian countries. The reason(s) for this geographic difference is not known.

Symptoms

- People with CLL may experience the following symptoms. Sometimes, people with CLL do not show any of these symptoms. Or, these symptoms may be caused by a medical condition that is not cancer. If you are concerned about a symptom on this list, please talk with your doctor.

- Swelling of lymph nodes in the neck, under the arms, or in the groin. This symptom is probably the most common one that patients with CLL first notice.

- Discomfort or fullness in the upper left part of the abdomen, due to enlargement of the spleen

- Fatigue (extreme tiredness)

- Fever and infection

- Abnormal bleeding

- Weight loss

Patients with CLL have a poorly regulated immune system, and their bodies can sometimes make abnormal antibodies against their own red blood cells and/or platelets, destroying these cells and resulting in anemia (low levels of red blood cells) or a low platelet count. These are called autoantibodies. This process can occur at any time during the course of the disease and is not necessarily related to the severity of CLL.

Diagnosis

The following tests may be used to diagnose CLL:

Blood tests. The diagnosis of CLL begins with a complete blood count (a routine blood test) to measure the counts of different types of cells in a person’s blood. If the blood contains high levels of white blood cells, CLL may be present. During the initial evaluation, the doctor will look at the blood smear under a microscope to determine which types of white blood cells are increased. Most patients with CLL initially have no symptoms and are diagnosed because an elevated lymphocyte count is detected on a complete blood count done for other medical reasons.

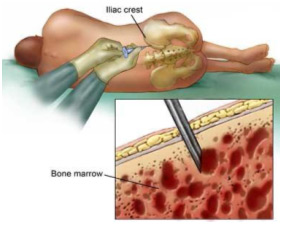

Bone marrow biopsy. In a bone marrow biopsy, a doctor takes a sample of marrow, usually from the back of the hipbone, with a needle. The cells from the marrow, along with the cells from the blood, are analyzed by a pathologist.

CLL can usually be diagnosed from studies of the blood, and a bone marrow biopsy is not needed in all patients. In some patients, it may be used to help determine a patient’s prognosis (chance of recovery) or provide further information about the reasons that other blood counts may be abnormal. Bone marrow biopsy. In a bone marrow biopsy, a doctor takes a sample of marrow, usually from the back of the hipbone, with a needle. The cells from the marrow, along with the cells from the blood, are analyzed by a pathologist.

CLL can usually be diagnosed from studies of the blood, and a bone marrow biopsy is not needed in all patients. In some patients, it may be used to help determine a patient’s prognosis (chance of recovery) or provide further information about the reasons that other blood counts may be abnormal.

Flow cytometry and cytochemistry. In these tests, cancer cells are treated with chemicals or dyes that provide information about the leukemia and its subtype. CLL cells have distinctive markers (cell surface proteins) on their surface. The pattern of these markers is called the immunophenotype. These tests are used to distinguish CLL from other kinds of leukemia, which can also involve lymphocytes. Both tests can be done from a blood sample.

Imaging tests. It is known that CLL is generally present throughout many parts of the body, even if the disease has been diagnosed early. Thus, imaging tests to determine if the cancer has spread are not needed in all patients, although they may be recommended at times to determine whether particular symptoms may be related to the CLL and to measure response to treatment.

An x-ray (picture of the inside of the body) may show if cancer is growing in lymph nodes in the chest.

A computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan (a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body) can detect affected lymph nodes around the heart, windpipe, lungs, and abdomen. CT scans can also determine if other organs, such as the spleen, are affected.

Treatment

The treatment of CLL depends on the patient's stage, risk status, and overall health. In many cases, a team of doctors will work with the patient to determine the best treatment plan.

Because CLL often progresses slowly, many people may not require treatment right away, and some may never require treatment at all. Although the available treatments can be highly effective, none of the standard therapies are capable of eliminating all of the CLL, and patients are not cured of their disease with treatment.

For some patients, symptoms and/or the presence of large amounts of CLL in the blood, lymph nodes, or spleen require treatment shortly after the diagnosis is made. In other patients, however, it is possible and advisable to observe the patient without treatment. During this time, the patient's blood counts are monitored and a physical examination is performed. Multiple studies have shown that no harm comes from the watch-and-wait approach (also called active surveillance), as compared with immediate treatment of patients with early-stage CLL. Some patients remain without symptoms for years, or even decades, and will not need any treatment.

Treatment is recommended for patients who develop symptoms and/or worsening blood counts. These might include increasing fatigue, night sweats, enlarging lymph nodes, or falling red blood cell or platelet counts. Patients with CLL are encouraged to talk with their doctors about whether their symptoms require treatment, balancing the benefits of treatment with side effects that may result.

Types of treatment for CLL

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs travel through the bloodstream to cancer cells throughout the body. When treatment begins, doctors may use a number of different drugs depending on the stage of the disease and the person’s age and health. Chemotherapy can be given in pill form and taken by mouth, by intravenous (IV) infusion, or by subcutaneous (SQ) injection (an injection under the skin). Sometimes a doctor may use a combination of drugs, but a combination of drugs is not always better than a single drug.

One of the first drugs patients with CLL may receive is called fludarabine (Fludara). Fludarabine belongs to a class of drugs called nucleoside analogues. Other nucleoside analogues, including pentostatin (Nipent) and cladribine (Leustatin) are also sometimes used to treat patients with CLL, although fludarabine is used more commonly.

Chlorambucil (Leukeran) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan or Neosar) belong to a class of drugs called alkylating agents. Both drugs can be given orally, while cyclophosphamide can also be administered intravenously. Prednisone (available under many brand names) is a type of oral corticosteroid that is often given together with chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide. In the past, patients were initially treated with either fludarabine alone or chlorambucil/prednisone, switching to the alternative regimen if the initial treatment did not produce sufficient benefit. Current studies are evaluating whether using these drugs together (in particular, combining fludarabine and cyclophosphamide) might be preferable. In addition, other studies are evaluating the benefit of adding rituximab (Rituxan) (see below) to fludarabine alone or to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide.

The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor is often the best way to learn about the medications you've been prescribed, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications.

Biologic therapy

Biologic therapy is the use of substances (made by the body or created in a laboratory) to support or stimulate the body’s immune system to fight the cancer. This may be called immunotherapy.

Rituximab is a monoclonal (synthetic) antibody that is given intravenously and binds to a protein on the surface of B cells, killing some of the CLL cells and potentially increasing the effect of chemotherapy. As mentioned above, rituximab is currently being evaluated in combination with chemotherapy.

Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) is another monoclonal antibody that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use with advanced CLL that is no longer responding to other treatments. It can be used in both T-cell and B-cell CLL. This antibody can be given either intravenously or as a subcutaneous injection.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is not used frequently in patients with CLL because the disease is located throughout the body. Radiation therapy can, however, be very helpful in shrinking an enlarged spleen or swollen lymph nodes and eliminating symptoms that may be associated with such growths. Radiation therapy may cause fatigue, mild skin reactions, nausea, diarrhea, or constipation. Most side effects go away soon after treatment is finished.

Side effects of treatment

Chemotherapy for CLL can be associated with nausea and vomiting, although these symptoms can generally be prevented with appropriate use of antiemetic drugs. Doctors will also closely watch for decreases in normal blood counts, which can lead to an increased risk of infection (due to decreased neutrophils), bleeding (due to decreased platelets), and fatigue (due to anemia). To manage these side effects, some patients need transfusions of red blood cells and platelets or antibiotics to treat infections.

Decreases in blood counts following chemotherapy are sometimes more severe in patients with CLL than in other types of cancer because of the presence of CLL cells in the bone marrow. Patients receiving treatment are encouraged to ask their doctors about the symptoms they might experience, how such complications might be prevented, and how closely they should be monitored.

Sometimes, subcutaneous injections of white blood cell growth factors such as filgrastim (Neupogen), sargramostim (Leukine), or pegylated filgrastim (Neulasta) are used to increase the bone marrow production of normal white blood cells. Injections of epoetin (Procrit or Epogen) or darbepoetin (Aranesp) can be given to increase red blood cell production.

The initial infusions of rituximab and alemtuzumab are often accompanied by fevers and chills and usually disappear after the first few treatments.

One of the side effects of both CLL and its treatment is the risk of developing a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection. Doctors may call these opportunistic infections because these infectious agents take advantage of a weak immune system. In particular, patients with CLL often develop infections with herpes viruses, either in the form of cold sores or as herpes zoster (shingles). Herpes zoster can become quite painful and progress to a severe infection. Patients should inform their doctors immediately if they notice a rash or skin eruptions resembling hives that are often grouped together and form the appearance of a band across the chest or abdomen, or extend down the legs, arms, or face. These infections can be treated effectively with antiviral drugs and respond best when treated early.

Remission

The goal of treatment is to eliminate any symptoms associated with the CLL and to reduce the amount of remaining CLL as much as possible. A complete remission (CR) occurs when the doctor cannot find any evidence of cancer remaining after repeated testing. A partial remission (PR) is when there is some cancer remaining; this is the most common outcome following current methods of treatment of CLL. With a PR, patients can feel quite well with normal blood counts, have no swollen lymph nodes or spleen, but still have considerable amounts of CLL remaining as can be detected by examination of the bone marrow biopsy with a microscope.

The goal of newer, more intensive treatments is to produce much greater decreases in the levels of cancer cells in the hope of prolonging survival. In the future, the definition of a CR in CLL is likely to change with advances in technology. For example, some sensitive tests can now detect extremely small levels of the abnormal DNA characteristic of CLL. This measurement is called a molecular remission.

Recurrent/refractory CLL

If leukemia is still obviously present after initial treatment, the disease is referred to as refractory CLL. CLL cannot be reliably cured using currently available standard therapies, and the disease generally recurs (comes back). The length of response can vary from weeks to many years, and the pace of regrowth of the disease can vary considerably. Detection of relapse does not mean that treatment is needed immediately, and a period of observation (watch-and-wait approach) is usually advisable, with treatment offered if the disease begins to cause symptoms again. If CLL becomes resistant to one chemotherapy agent, treatment with other types of drugs is recommended.

Some symptoms can be treated with other approaches, examples of which include radiation treatment or a splenectomy (surgery to remove an enlarged spleen). Some patients who experience recurrent infections may benefit from monthly intravenous infusions of immunoglobulin because patients with CLL have reduced amounts of normal antibodies. Patients who develop antibodies that destroy their own blood cells (see above) are often treated with high doses of corticosteroids to reverse this process.

St em cell transplantation

Patients with CLL treated with chemotherapy and/or biologic therapy inevitably have the disease return, since these treatments do not cure CLL. These patients may be considered for stem cell transplantation (SCT). This treatment is now being studied closely as an effective treatment for CLL, particularly for younger patients, but is still considered experimental. Because there are significant risks to this treatment approach, the doctor will consider several factors, including the patient's age and general health, before recommending this approach.

Hematopoietic stem cells are special cells that can develop into different kinds of blood cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Stem cells are found both in the circulating blood and in the bone marrow. In a SCT, the patient's bone marrow is treated with high doses of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy to get rid of as many leukemia cells as possible and to prevent the immune system from reacting to and rejecting the donated stem cells.

In an allogeneic transplantation, stem cells obtained from a tissue-matched donor are transfused into the patient's bloodstream. The donor and recipient can have different ABO blood types, but must have the same human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type. Most often, an HLA-matched sibling is the stem cell donor. Over two to three weeks, these cells engraft (begin to make new blood cells) and turn into healthy, blood-producing tissue. Destroying the patient's own marrow reduces the body's natural defenses, temporarily leaving the patient at increased risk for infection. Until the patient's immune system is back to normal, patients may be hospitalized and may need antibiotics and transfusions of red blood cells and platelets.

The major risk of allogeneic transplantation is that the donor’s immune cells will recognize the host tissues as "foreign," causing graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). GVHD is a serious complication of allogeneic transplantations and can be fatal. Other side effects include liver abnormalities, diarrhea, infection, rashes, and organ damage.

In some patients, reduced-intensity transplant (sometimes termed mini-transplant) is an option. During a mini-transplant, the amount of chemotherapy given to destroy the bone marrow is less than a standard transplantation. Once the donor cells engraft, the hope is that the donor cells will destroy the leukemia cells in what is called the graft-versus-leukemia effect. This procedure still includes risks, the most significant one being the development of long-term GVHD.

Side Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cancer and cancer treatment can cause a variety of side effects; some are easily controlled and others require specialized care. Below are some of the side effects that are more common to CLL and its treatments.

Constipation. Constipation is the infrequent or difficult passage of stool. About 40% of patients in palliative care (care given to improve a patient’s quality of life) experience constipation, and about 90% of patients taking opioid medications (such as morphine) experience constipation. Constipation includes fewer bowel movements, stools that are abnormally hard, discomfort, or a feeling of incomplete rectal emptying. Patients with constipation can experience pain, swelling in the abdomen, loss of appetite, nausea and/or vomiting, inability to urinate, and confusion.

Fatigue. Fatigue is extreme exhaustion or tiredness and is the most common problem patients with cancer experience. More than half of patients experience fatigue during chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and up to 70% of patients with advanced cancer experience fatigue. Patients who feel fatigue often say that even a small effort, such as walking across a room, can seem like too much. Fatigue can seriously affect family and other daily activities, can make patients avoid or skip cancer treatments, and may even affect the will to live.

Hair loss (alopecia). A potential side effect of radiation therapy and chemotherapy is hair loss. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy cause hair loss by damaging the hair follicles responsible for hair growth. Hair loss may occur throughout the body, including the head, face, arms, legs, underarms, and pubic area. The hair may fall out entirely, gradually, or in sections. In some cases, the hair will simply thin—sometimes unnoticeably—and may become duller and dryer. Losing one's hair can be a psychologically and emotionally challenging experience and can affect a patient's self-image and quality of life. However, the hair loss is usually temporary, and the hair often grows back.

Infection. An infection occurs when harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi (such as yeast) invade the body, and the immune system is not able to destroy them quickly enough. Patients with cancer are more likely to develop infections because both cancer and cancer treatments (particularly chemotherapy and radiation therapy to the bones or extensive areas of the body) can weaken the immune system. Symptoms of infection include fever (temperature of 100.5°F or higher); chills or sweating; sore throat or sores in the mouth; abdominal pain; pain or burning when urinating or frequent urination; diarrhea or sores around the anus; cough or breathlessness; redness, swelling, or pain, particularly around a cut or wound; and unusual vaginal discharge or itching.

Mouth sores (Mucositis). Mucositis is an inflammation of the inside of the mouth and throat, leading to painful ulcers and mouth sores. It occurs in up to 40% of patients receiving chemotherapy. Mucositis can be caused by chemotherapy directly, the reduced immunity brought on by chemotherapy, or radiation therapy to the head and neck area.

Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting, also called emesis or throwing up, is the act of expelling the contents of the stomach through the mouth. It is a natural way for the body to rid itself of harmful substances. Nausea is the urge to vomit. Nausea and vomiting are preventable, treatable, and may occur in patients receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Many patients with cancer say they fear nausea and vomiting more than any other side effects of treatment. When it is minor and treated quickly, nausea and vomiting can be quite uncomfortable but cause no serious problems. Persistent vomiting can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, weight loss, depression, and avoidance of chemotherapy.

Neutropenia. Neutropenia is an abnormally low level of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. All white blood cells help the body fight infection. Neutrophils fight infection by destroying bacteria. Patients who have neutropenia are at increased risk for developing serious bacterial infections because there are not enough neutrophils to destroy harmful bacteria. Neutropenia occurs in about 50% of patients receiving chemotherapy and is common in patients with leukemia.

Skin problems. The skin is an organ system that contains many nerves, so skin problems can be painful. Many patients find skin problems especially difficult to cope with because the skin visible to others. Because the skin protects the inside of the body from infection, skin problems can often lead to other serious problems. In other cases, treatment and wound care can often improve pain and quality of life. Skin problems can have many different causes, including chemotherapy leaking out of the intravenous (IV) tube, which can cause pain or burning; peeling or burned skin caused by radiation therapy; pressure ulcers (bed sores) caused by constant pressure on one area of the body; and pruritus (itching) in patients with cancer, most often caused by leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, or other cancers. As with other side effects, prevention or early treatment is best.

Thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia is an unusually low level of platelets in the blood. Platelets, also called thrombocytes, are the blood cells that stop bleeding by plugging damaged blood vessels and helping the blood to clot. Patients with low levels of platelets bleed more easily and are prone to bruising. Platelets and red and white blood cells are made in the bone marrow, a spongy, fatty tissue found on the inside of larger bones. Certain types of chemotherapy can damage the bone marrow so that it does not make enough platelets. Thrombocytopenia caused by chemotherapy is usually temporary. Other medications used to treat cancer may also lower the number of platelets. In addition, a patient's body can make antibodies to the platelets, which lowers the number of platelets.

After Treatment

After treatment for CLL ends, talk with your doctor about developing a follow-up care plan. This plan may include regular physical examinations and/or medical tests to monitor your recovery for the coming months and years.

Patients should receive regular follow-up examinations for several years to detect evidence of relapse or late effects (side effects that occur years after treatment) of chemotherapy. Patients with CLL are also at a higher risk of developing other tumors, particularly lung, colon, or skin cancers. Patients should inform their doctors if they notice new or worsening skin lesions or moles.

People recovering from CLL are encouraged to follow established guidelines for good health, such as maintaining a healthy weight, eating a balanced diet, and having recommended cancer screening tests. Talk with your doctor to develop a plan that is best for your needs. Moderate physical activity can help rebuild your strength and energy level.

Amazon will work with you and our India

Affiliates to create a package where all your Cancer

concerns/problems can be addressed. If you have any

questions, please do not hesitate to contact us by

phone or email.

|